‘You’re an artist and time is your paint’

Billy Hardeman

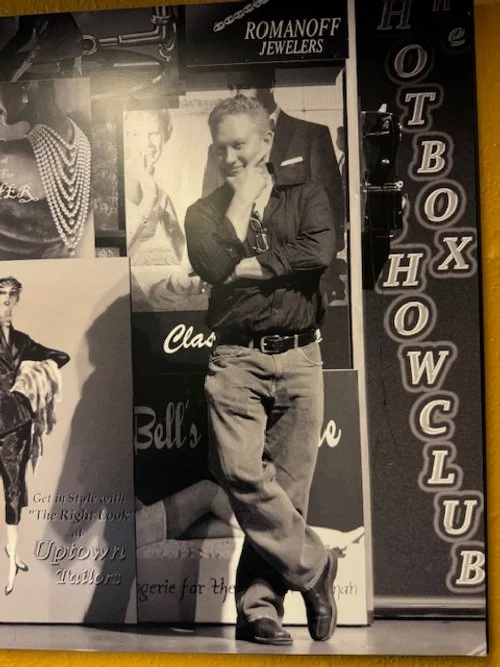

Phoenix Theatre Company’s creative director Michael Barnard, left, and business manager Vincent VanVleet.

By Mary L. Dudy and Stephane Fitch

Other cities may have more celebrated theatrical landscapes, but Phoenix has Michael Barnard. After a five-year stint with Disney, Barnard took the theater director spot at the Phoenix Theatre Company in 1999 and has since transformed it into one of the country’s most successful regional theaters. He’s now overseeing a $30 million expansion. We asked him to tell us what it means to control time onstage — and sometimes be dominated by it offstage.

How long have you been in the theater?

The very first show I was in was “Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer.” We did it inside our first grade classroom. I played the title role. As I heard the applause from my own parents and the other kids’ parents, I knew right then and there that I was bit.

How did you go from actor to director?

At 14, I was involved with a summer theater program through the city of Glendale, Arizona, which I continued doing until I aged out. At that point the group I’d been with and I decided to start our own theater company. My grandfather had left me some money in his will, so I used it to invest in the musical “Applause.” When our original director and choreographer both had to drop out, the troupe said, “Well, you got us into this mess, how are you going to get us out?” So there I was at age 20 directing and choreographing my first musical. By the time I graduated from college, I’d directed a number of shows. It was such a great experience that I wound up getting a master of fine arts in directing from Northwestern.

Michael Barnard

What does the timeline for putting on a play look like?

I’m currently working on getting licenses for shows three years out. The next step is putting together artistic teams, hiring directors, choreographers, designers, etc., which has to be done far enough out to get a commitment from people. Six or seven months out we start production and design elements. Four to five months out we go to New York, Chicago or LA to start casting if we don’t feel there’s anyone in the Valley who can play the roles. At the same time, we’re doing budget assessments and placing orders. The scenic elements have to be ordered well in advance because supplies are slow right now. The director, choreographer and musical directors break the show down into categorical hours.

It sounds like the clock ticks faster and faster, and you haven’t even gotten to rehearsal!

Three and a half weeks out we go into rehearsal, and we’ve got tech for half a week. We can rehearse eight hours a day, six days a week. Union rules say that you have to take a 10-minute break every hour and 20 minutes — or a 5-minute break every 55 minutes, or you can do a straight six, with a 20-minute dinner break. Or you can have seven hours of rehearsal and an hour for dinner. That’s your week, six days a week.

Is your time union protected?

[Laughs] No! I honestly can tell you that Vincent [VanVleet, PTC’s executive director] and I being married and together for 25 years is the only way this theater would have survived. We work 7 days a week.

How do you know how long an act should be?

That subject always comes up. Your act is as long as it takes to tell your story. As long as you can keep your audience engaged it doesn’t matter if that show is an hour and 20 minutes long and this one’s 64 minutes. You’re an artist, and time is your paint.

Are there plays or musicals that are inherently difficult to stage?

Anything that has flying in it. “Mary Poppins,” “Peter Pan,” “The Wizard of Oz” are always difficult. Safety is a huge issue. It eats up time.

How about historical time? Is it still possible to stage favorites from bygone eras?

It’s very tricky choosing classic work. We learn something about perspectives that teach us about our history and who we are. You are now a product of all of the experiences you had in the past. But there are a lot of people who attend the theater who don’t want to feel that they are being blamed for certain things that are happening in this country. Politics have gotten in the way. As a country, we are so polarized.

Has time been good to the theater, would you say?

It’s a difficult time. There are companies that used to bring in $30 million a year that have dwindled to $2 million a year. Steppenwolf (Theatre in Chicago) just let go of 37% of their staff. Paper Mill (Playhouse in New Jersey) is struggling. Oregon Shakespeare Festival almost completely collapsed. It’s happening all over the country.

If you had a time machine and could go back to any moment in the theater, where would you go?

The ’50s was a great time for theater, a golden era. It was before television. Moviemakers were making a lot of musicals, so movies and the theater served each other because people love to be entertained. The theater is a business now. Actors have to have agents and managers just to get into auditions. In the ’50s a fresh new personality could get a start. The old saying about “being in the right place at the right time” no longer applies.

People are usually asked about what they wish they had more time for. What do you wish you had less time for?

Looking for money and trying to solve HR problems. We’re in a very dramatic industry. This happens all the time. I don’t know that I’ve ever not walked into the theater thinking I was going to do one thing and then dealing with something else. In this industry, you are on a time clock all the time.

RSP Architects

The Phoenix Theatre Company broke ground in September on a $30 million expansion of one of its three stages.

As a professor of English literature, Mary L. Dudy’s conversations with Shakespeare required her to unwind centuries of scholarly work. As a journalist, Stephane Fitch spent two decades battling clocks ticking down to tight deadlines. Read more about them or this series of interviews about time.